Since 2014, Indonesia’s domain name registry (PANDI) has overseen the registration of .id domain names, following the earlier country code top-level domains (ccTLDs), such as .co.id, .or.id, and .go.id. PANDI has recently reported on the growth of .id domain names in 2019, which saw an increase in registrations of about 45%, reaching a total of 135,000 registrants.

An Indonesian Internet Providers Association (APJII) nationwide survey found that the number of internet users in Indonesia increased by 14.6 percent to 196 million people in the period between 2019 and Q2 2020, up from 171 million in 2018. The survey also revealed that Indonesia’s internet penetration rate has gone up to 73.7 percent. This means that the country is catching up with neighboring Brunei, Singapore, and Thailand, whose internet penetration rates exceeded 70 percent last year. Part of this increase seems to be related to the limitation of in-person activity in the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak.

This internet usage growth has also meant a higher incidence of cybercrimes and online disputes, including over domain names. According to the domain name dispute statistics from WIPO, there have been 274 generic top-level domain name disputes involving Indonesian respondents to date. Meanwhile, 18 cases have so far been decided by PANDI’s Domain Name Dispute Resolution (PPND) in fights against Indonesian ccTLD cybersquatters, third parties who attempt to register domain names using the trademarks of others. PPND, a non-litigation dispute settlement body for disputes over Indonesian internet domain names, handles domain name disputes related to trademarks, registered names or regarding matters of decency. The examination of such disputes is conducted by PPND panel(s).

PANDI’s Domain Name General Policy version 6.0, dated February 25, 2019, explains the five categories of.id domain names: normative, trademark-related, product- or service-related, distributorship-related, or institutional.

Ministry of Communication Regulation No. 23 of 2013 regarding Domain Name Management stipulates that a registered trademark holder is entitled to register, use, and benefit from Indonesian ccTLDs. Based on PANDI’s naming guidelines, a trademark registration or application is required if the applicant claims that the domain name is related to their trademark. However, in practice, the registrar typically only requires a copy of the registrant’s ID card to proceed with the .id domain name registration, because the registrar may choose another naming criterion that does not require a trademark or other IP ownership. This may lead to the registration of .id domains by cybersquatters.

Procedures

PPND welcomes any trademark holder to file a complaint regarding domain names violating their registered trademark, before filing litigation with the court.

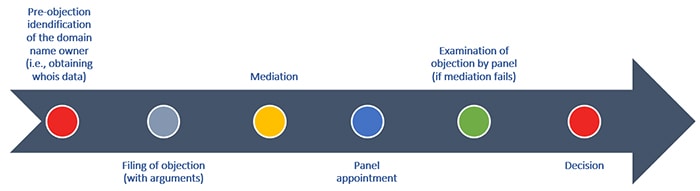

The current PPND policy (version 7.0) requires that every claimant file a pre-objection as the first step. The pre-objection phase includes a request for the whois data, which reveals the owner of a domain. Obtaining the results takes around three days after the pre-objection documents are completed and accepted by PPND. Upon receiving the pre-objection result, the next step is filing an objection laying out pertinent arguments. PPND may then proceed to mediation, followed by examination of the objection.

The simplified timeline below shows the key steps in the process.

Under normal circumstances, the whole process may take around 2–3 months to be decided. An unsatisfied party that disagrees with the PPND decision may file a lawsuit with the court.

Possible Arguments

A claimant requesting a domain name take-down or transfer in accordance with the PPND policy must prove all of the following conditions:

- The domain name is identical or confusingly similar to a trademark;

- The registrant has no rights or legitimate interests in the domain name; and

- The domain name has been registered and is being used in bad faith.

Of these three concurrent claims, the most challenging one to prove is the bad-faith intent. Nonetheless, it is essential. Even if a claimant can show valid trademark ownership and prove that the domain name in question was filed by an unauthorized entity, the PPND panels will refuse the claim if evidence of bad faith is lacking.

The strongest evidence of bad faith is any request (e.g. text message, email, etc.) by the registrant for compensation for transferring the domain name. Such evidence is straightforward proof that the registrant intended to sell, lease, or transfer the domain name for his or her financial benefit. However, of the 18 cases decided by the PPND since its inception, only seven were able to prove the registrant’s intent to sell the domain name for financial benefit.

There are other types of actions that are considered bad faith as well. For example, bad faith can be proven by showing that the registrant intends to prevent the trademark owner to use the contested domain name (i.e., parked domain), or by showing that the registrant intended to damage the trademark owner’s business activities. In addition, a domain name registrant intending to attract the internet user to another online location for illegal financial benefit would be another clear indication of bad faith.

Case Study

When the well-known video streaming service Netflix found that neflix.id had been registered by an unauthorized Indonesian citizen using their well-known trademark, they brought the matter before the PPND.

As the company had already registered their trademark in Indonesia, Netflix was able to prove that netflix.id was filed by an unauthorized party. However, no proof of intent to sell was forthcoming, so Netflix made the accusation that netflix.id was a parked domain, with the registrant trying to prevent Netflix from registering and using the domain name in Indonesia.

In his reply, the registrant pointed out that Netflix had not secured netflix.id before, and argued that in light of the “first to file” domain name registration principle, Netflix should have registered the domain name as soon as they were eligible to do so. The PPND, however, disagreed, deciding that the claim had in fact proved the three necessary conditions simultaneously. Hence, netflix.id was transferred to Netflix’s ownership.

Conclusion

Just as well-known brands are targeted by intellectual property infringers, these brands can also be targeted by parties wishing to benefit from their reputation or name recognition through a domain name. The process of acting against this in Indonesia is not simply a matter of trademark enforcement, but is a separate process governed by a different set of laws and regulations. Brand owners should be aware that having a trademark portfolio and strategy is often not enough; rather, they need a comprehensive and strategic awareness of how to manage all of their current and potential assets, including virtual properties such as domain names.