Patent is an essential piece of the amended Law on Intellectual Property (“Amended IP Law”), which was passed by the National Assembly of Vietnam on June 16, 2022, and will take effect on January 1, 2023 (except for the regulation on protection of experimental data for agrochemical products, which will take delayed effect on January 14, 2024).

Among the amended and supplemented contents of the Amended IP Law, there are notable patent-related amendments to Article 60 on assessing the novelty of inventions and Article 96 on grounds for invalidating patent protection titles. We discuss these changes below.

Secret Prior Art Under Article 60.1

A significant amendment to Clause 1, Article 60 of the Amended IP Law on the novelty of inventions is to broaden the scope under which an invention can be considered to have lost its novelty.

For the first time in Vietnam, “secret prior art” –a patent application with an earlier filing date or priority date but published on or after the filing date or priority date of an examined patent application – is introduced as a prior art document.

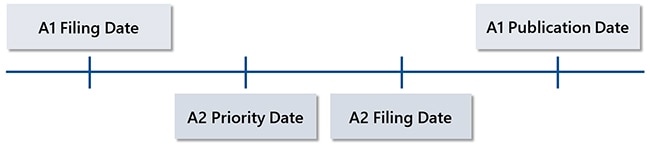

In the diagram above, at the time of filing of the A2 application, secret prior art A1 has been filed but not yet published, making it inaccessible to the public. At this point, only the A1 applicant and the IP Office are aware of the A1 application.

Under the current provisions of the 2005 IP Law, as amended in 2009 and 2019, the A1 patent application is not eligible to be a prior art document when assessing the novelty of A2. However, based on the “first-to-file principle” and the principle of priority, the IP Office has still had other approaches to bar the patentability of an A2 patent application if there is such an A1 application.

By supplementing the provisions of Article 60.1(b) of the Amended IP Law, the A1 patent application can officially be considered “secret prior art” to assess the novelty of A2. As a result, this amendment provides a more legitimate, direct, and comprehensive tool for assessing novelty using “secret prior art.”

From the provisions of the amended Article 60.1, there are still some ambiguities, such as whether secret prior art is limited to the case where the applicants of A1 and A2 are different (in some countries, secret prior art does not apply if the applicants of A1 and A2 are the same), and whether there is a “domestic limitation,” in which patents filed abroad and not yet published are not considered to be secret prior art in Vietnam. After the Amended IP Law goes into force, the authorities will likely issue more guidance to clarify these ambiguous issues.

Finally, one can see that the provision on the use of “secret prior art” applies only to the assessment of novelty of an invention, not to the degree of inventive step.

New Grounds for Patent Invalidation Under Article 96

Article 96 has been amended to include additional grounds for patent invalidation. The two current grounds are (i) the applicant did not have the right, or did not have the right transferred to him or her, to register the invention, or (ii) the subject matter of the invention did not meet the protection criteria. The Amended IP Law adds the following provisions:

(iii) A patent is invalidated in its entirety if:

- The patent application is filed in violation of the security control regulations, or

- The invention is directly created based on genetic resources or traditional knowledge about genetic resources but the patent application does not disclose or incorrectly discloses the origin of the genetic resources or traditional knowledge about genetic resources contained in that application.

(iv) A patent is invalidated in whole or in part if:

- An amendment expands the scope of the disclosed subject matters or changes the nature of the subject matters claimed in the application;

- The invention is not sufficiently and clearly disclosed in the specification;

- The patented invention extends beyond the scope of the disclosure in the original specification; or

- The invention does not meet the first-to-file principle.

In practice, a number of invalidators have cited these grounds in the past in their patent invalidation requests, but as far as we know, the IP Office has not yet used these factual grounds in any judgment to invalidate a patent. This is the first time that these grounds have been codified in law in Vietnam, which could lead to them being used more often in invalidation requests.

The non-protection of inventions filed in contravention of the provisions on security control is mentioned in the current regulations. However, there are still some unclear and controversial points, such as the identification of “Inventions of Vietnamese organizations and individuals” and “inventions created in Vietnam” as the objects of security control.

The Amended IP Law makes the provisions on security control a basis for invalidating a patent if the patent application is filed in violation of this provision, and it also replaces the above ambiguous terms with a clearer term: “Inventions in technical fields that have an impact on national defense and security, created in Vietnam, and under the registration right of an individual who is a Vietnamese citizen and permanently resides in Vietnam, or of an established organization under Vietnamese law.”

More specific guidelines, however, are still needed to accommodate cases such as inventions partially created in Vietnam; inventions jointly owned by Vietnamese entities and foreign entities; inventions created in Vietnam under the right of registration of Vietnamese entities but transferred to foreign entities before filing, and so on.

The protection of genetic resources and traditional knowledge about genetic resources is provided for in Law on Biodiversity No. 20/2008/QH12, as amended by Law No. 35/2018/QH14. The introduction of regulations on disclosure of genetic resources or traditional knowledge about them in patent applications is in line with the trend of using such resources to create new technical solutions. This provision is intended to add additional measures to avoid the loss of said genetic resources in addition to those provided for in the Law on Biodiversity.

Although not a new concept, the provisions on disclosure of genetic resources or traditional knowledge of genetic resources in patent applications are not mentioned at all in the current IP Law. Therefore, there should be specific guidance on the information to be disclosed in the description, how to assess the disclosed information in the procedure for invalidating a patent based on this ground, etc.

Although mentioned as requirements during the examination of a patent application, the grounds relating to disclosure, amendment of a patent description, or the first-to-file principle have never been recognized as a basis for patent invalidation in the IP Law. It is entirely reasonable to include these grounds for invalidation in the Amended IP Law; however, several parts of the implementation remain unclear, such as the procedure and authority to define a “person of ordinary skills in the respective art.”

Conclusion

In our opinion, the Amended IP Law, which has received a lot of feedback from IP practitioners, is a progressive document that introduces many necessary and reasonable changes for the IP environment in Vietnam. However, there are still some ambiguities that require more clarification and professional advice on how to comprehend and implement these new patent provisions. We believe that the Vietnam IP Office will hold dissemination sessions and discussions on how to apply the Amended IP Law.